Freedom Within Limits in a Montessori Class

One of the most common misunderstandings about Montessori education surrounds the freedom we give the children in our care. Once someone steps inside a classroom and observes, there is no doubt, and all misconceptions are quickly cleared up.

Montessori isn’t a trademarked concept though. Anyone (school or individual) can claim to be “Montessori” but that doesn’t necessarily make it so. This is why specific, high-quality teacher training programs, along with affiliation or accreditation with a major Montessori organization (such as AMI or AMS) is critical to ensuring a high fidelity program.

Montessori philosophy relies heavily on freedom of choice. We also rely heavily on appropriate limits. There is a critical balance, and achieving this balance is what gives children the sense of dignity, empowerment, and success they deserve. Children thrive when given independence in developmentally appropriate ways that support their growth. A foundation of respect for self, others and the classroom materials are foundational in a Montessori environment, no matter the age of the children within.

What does this look like in our learning environments, and how might parents utilize these strategies in the home? Read on to learn more.

The physical boundaries of the environment

Montessori schools and guides are very intentional in the ways they structure the physical classroom environment. We want our students to be able to move freely around the space, but we don’t want that movement to inspire behaviors that are distracting to others or unsafe. The good news is there are plenty of things we can do to ensure choice, safety, and learning, all at the same time.

In classrooms for younger children, we avoid having wide open spaces that invite running indoors. The wooden shelves that house learning materials are strategically placed to block paths that children may otherwise utilize in that way. Instead, we provide indoor-appropriate movement opportunities, we teach children how to use them, and we make sure they are in spaces that don’t disrupt the work of others. We also make sure there is time and space built into the day that allows for running outside.

Dr. Montessori valued the opportunities available to children outdoors and in nature, so our schools work hard to provide appropriate and safe space for children to explore. This looks vastly different depending on the child. A four-year-old might enjoy a fenced-in area with raised garden beds, trees, and grassy fields. An 11-year-old might walk to an adjacent wooded area under the supervision of an adult where they independently gather materials with peers to make forts and other structures.

Choosing what to work on

As adults, we don’t like to be micromanaged. Neither do children. Even a small degree of autonomy allows a person to feel like their decision-making is valued and trusted. This overarching idea is kept in the forefront of our minds, but it does look different at different levels.

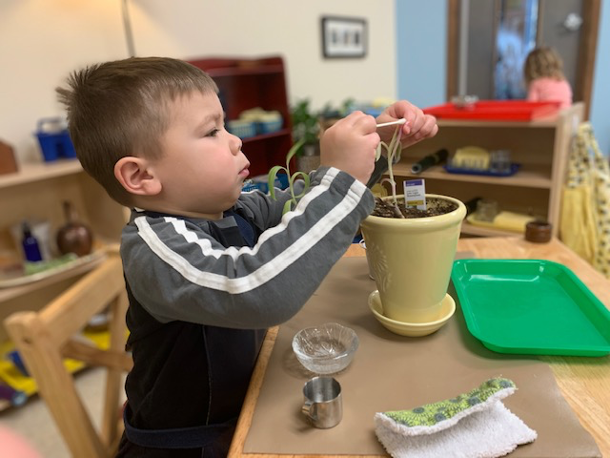

During the first plane of development (newborn - age 6) children are given presentations on how to use various materials and complete various tasks. During their independent work cycle they are generally permitted to choose which of these tasks they would like to repeat and in what order. This allows them to follow their interests and develop skills they are internally primed to master without being tethered to a prescribed one-size-fits-all program. As they enter the final year or this period, their guide may start to implement some of the structures seen in the second plane to ease their transition and provide for evolving developmental needs.

During the elementary years, there are certain academic expectations. Children in Montessori environments are given regular lessons on topics of interest as well as to teach basic math and language skills. They are still able to choose their work, as well as make choices about what they would like to spend more time on and to study in depth. Our guides are watching closely, however, to make sure children do not avoid subjects. (More on that later in this article)

Honoring personal health needs

We don’t believe children should have to ask permission to address their own basic needs. Whether it be using the toilet, getting a drink of water, or having a snack, all people (children included) should be able to listen to their own bodies and care for those needs on demand.

When children are very young, they need more assistance, but we teach them to listen to their bodies’ cues and guide them through the processes. As they get older and more independent, we build structures into the environment that allow them to meet their needs independently. Even as young as age three, children serve themselves a snack if a seat is available at the snack table. They know where their water cup is located and how to clean up a spill if it happens. The restroom is in the classroom or nearby so that they can use it without the help of an adult.

Multiple winning options

Want to give kids choice while still achieving specific goals? Give win-win options. We use this strategy in the classroom, but parents can use it at home as well. Some examples:

“Would you rather get dressed or eat breakfast first?”

“I need help with some of the chores. Are you in the mood for washing dishes or doing laundry?”

“It’s almost bedtime. Please go get into your pajamas and brush your teeth, and any time you have leftover before 8:00 we can use to read together.”

“You need to pack some more protein in your lunch for tomorrow. Would you like sliced turkey or some hummus?”

Keep in mind that fewer options make decision-making easier. This is especially important to consider when a child is younger or if the decision is causing any kind of stress.

Guidance and discussion

As children get older, it’s important to be transparent in the process of offering increasing freedom. We tell children that we value their input, that we want them to blaze their own trails, and that we are here to support them on the journey.

Remember above when we talked about addressing when a child avoids a particular subject? There are many reasons why they might do so, but it’s usually because the skill is too challenging or too easy. By observing the child at work, we can often get an idea of what’s going on, but with children elementary-aged and older, a conversation can be incredibly enlightening.

Once we find out why the avoidance is occurring, we can help develop a plan. The child may need to be introduced to time management strategies. They may need a refresher lesson. They may need to be challenged in a whole new way. Montessori schools are structured so that opportunities for these quick but important check-in meetings are frequent. Long blocks of time dedicated to learning and working independently, coupled with a variety of goals that extend far beyond academics, allow students and guides to work together toward productive independence.